Improving Value

Hospital/Physician Rate Setting

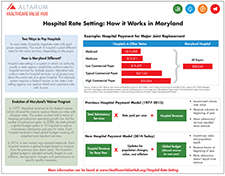

Rate setting was introduced as a method to curb hospital expenditures while improving payment equity and reducing price variation. While more than half of U.S. states at one point had programs to review or regulate hospital rates, Maryland has the only remaining statewide all-payer hospital rate setting program.

The system used by Maryland has been found to lower rates of annual hospital spending, while providing a platform for quality improvement and a potential reduction in administrative burden. Maryland’s program also has reduced cost-shifting between public and private payers, enhanced access to care for uninsured patients (because uncompensated care is built into hospital rates so hospitals have a way of financing it) and added to the financial stability of hospitals. More recently, Maryland has broadened the impact of its program by proactively treating chronic conditions and forming regional partnerships to organize care management within geographic areas.

In most states, hospitals negotiate payment rates with each payer. Payers can include private health insurance plans, self-insured employer plans, and uninsured individuals, and may also include public payers like Medicaid and Medicare.1,2

Hospital rate setting is a system in which an authority, usually a state agency, establishes uniform rates for hospital services for multiple payers. When every payer in the state participates—as is the case in Maryland—it is referred to as all-payer hospital rate setting.

A rate-setting system does not mean that all hospitals in the state receive the exact same payment. In Maryland, rates are set so that all payers pay approximately the same price for a given service at a given hospital. Payers pay on the basis of charges regulated by the rate-setting authority—but some payers, like Medicare, may pay slightly lower rates.

All-payer systems, such as Maryland’s, require a federal waiver in order for the state’s rate setting agency to replace Medicare’s payment rules with its own. The waiver requires the state not exceed the per admission amount that Medicare would have paid under its regular payment rules for hospitals.

What Value Problems Does Rate Setting Address?

Hospital care represents 32 percent of national healthcare spending.3 Annual increases in per admission spending has been identified as a major driver of medical spending, and even a modest decrease can mean annual savings of billions of dollars.4 A system that relies on the negotiating strength of each individual payer can leave smaller payers and the uninsured paying much higher prices for hospital services.5

A hospital rate setting system can contain costs by establishing payment levels and controlling the rate of growth of those payment levels over time. In theory, rate setting systems also should lower costs by reducing or eliminating the administrative burden of negotiating multiple payer contracts and could streamline claims processing. Perhaps most importantly, a rate setting system can provide a platform for payment reforms to promote improvements in the quality and equity of care. To the extent that quality incentives are built into the uniform payment rates, they apply to the full population of patients, rather than just an individual insurer’s population, increasing the incentive to deliver care more efficiently. Because spending flows and performance metrics are publicly debated, and the rate setting agency is usually required to report on overall hospital performance, these systems should be able to provide better price and quality transparency to consumers.

A more in-depth analysis of hospital/physician rate setting can be found in Hospital Rate Setting: Promising, but Challenging to Replicate, Research Report No. 1, Healthcare Value Hub (August 2017- updated from March 2015).

Notes

1. Bringing in public payers requires a waiver from the federal Medicare program and also that the state Medicaid system agreed to be a part of the payment system. In Vermont, for example, Medicaid decided not to participate in a proposed multi-payer system that was designed for them. Medicaid has to agree or be mandated to be a part of the system by the legislature.

2. Murray, Robert, “The Case for a Coordinated System of Provider Payments in the United States,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law Advance Publication, Vol. 37, No. 4 (August 2014).

3. CMS, National Health Expenditure Projections 2013-2023, http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/Proj2013.pdf

4. See Urban Institute’s Containing the Growth of Spending in the U.S. Health System, for more information. http://www.urban.org/publications/412419.html

5. Bai, Ge, and Gerard F. Anderson, “Extreme Markup: The Fifty U.S. Hospitals with the Highest Charge-To-Cost Ratios,” Health Affairs, Vol. 34, No. 6 (June 2015).