Healthcare Cost Drivers: High and Rising Unit Prices

Survey data consistently shows that healthcare costs are a top consumer concern.1 Not only do high prices make it difficult for people to fill prescriptions and schedule doctors’ appointments, but they may also force them to make deep financial and personal sacrifices, affecting their housing, employment, credit and daily lives.2

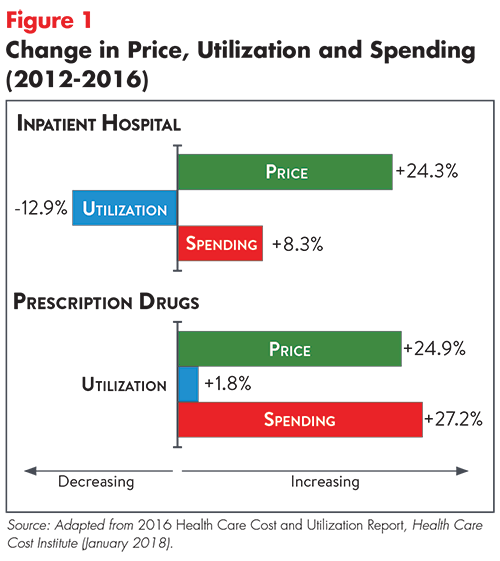

While many attribute high national healthcare spending to unnecessary use of services, strong evidence suggests that spending more per unit (as opposed to consuming too many units) of healthcare is the leading driver of high spending in the U.S. In fact, analyses show that rising unit prices have driven year-over-year increases in overall healthcare spending, despite the fact that service use has generally declined (see Figure 1).3 Rising unit prices also outweigh other drivers of per person spending growth, such as increasing prevalence of chronic disease and the aging of the population.4,5

Spending Drivers: Private vs. Public Coverage

In the employer-sponsored (or private) insurance market—which covered over 67 percent of U.S. residents in 20166—price increases drove the majority of spending growth for all major service categories from 2012-2016.7 As seen in Figure 1, price increases for prescription drugs and inpatient services were particularly large.8

Unit price growth is comparatively less of a problem in Medicare and Medicaid, where governmental payers are better able to curtail prices. These programs have experienced very low growth in per person spending in recent years, which economists attribute to successful efforts to coordinate and manage care for the “dual-eligible” population—low-income elderly patients who qualify for both Medicaid and Medicare. Historically, these patients have been a major driver of federal healthcare spending.9

Why are Unit Prices so High?

Some suggest that the higher prices in the private insurance market result from Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates that are too low.10 This is a matter of debate but, even if true in some situations, it does not explain why the U.S. spends so much more than other countries. Moreover, there is strong evidence that rising unit prices are largely driven by market power that enables providers, drug manufacturers and others to charge prices substantially above the cost of providing their goods or services.

Provider Prices

In the U.S., provider payment is determined in two very different ways. Within Medicare and Medicaid, unit prices are dictated through a formal process that incorporates input from stakeholders. For private insurers, provider prices reflect the relative market power of the insurer and provider.

Private insurer contracts often set provider payments as a multiple of Medicare rates—for example, 160 percent of the Medicare rate for a given service. But the negotiation process can result in very different multiples being used for providers in the same geographic area. For example, researchers have found that private payer hospital reimbursements can vary two-fold in the same city.11 Recent trends in provider consolidation have raised concerns that increased market power will lead to even higher provider payment rates.12

Prices for Drugs and Devices

The U.S. prescription drug market is complex and, for a variety of reasons, lacks the competitive forces that can help regulate prices in other sectors of our economy. Barriers to competition include patent protection, market exclusivity and natural monopolies for drugs treating diseases with patient populations that are too small to attract multiple manufacturers.13 Some drug makers also use controversial tactics to thwart competition, for example:

- obtaining patents on “new drugs” that are only slightly different from existing drugs with patents that have expired;

- abusing FDA rules in order to prevent generic manufacturers from obtaining samples of a drug; and

- paying generic competitors to delay entering the market with competing products.14

Medical devices can also be very expensive with little transparency in pricing and costs. For conventional devices, such as surgical gloves and other routine supplies, companies compete heavily on price to achieve high sales volumes. In contrast, markets for advanced products like implantable medical devices obscure prices, have barriers to entry and are much less competitive, allowing device companies to raise prices in order to increase profits. Price growth in this sector is difficult to assess because prices—except those for durable medical equipment—are embedded in estimates of provider spending and not broken out separately.15 However, prices for medical devices are likely growing, given that large medical device companies consistently report profit margins of 20 to 30 percent.

Conclusion

Healthcare price growth is the leading reason for high healthcare spending and contributes to significant “affordability burdens” for consumers. A 2017 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation revealed that almost one third of the U.S. population has gone without needed medical care due to cost concerns and more than one-quarter of those who received care struggled to pay the resulting medical bills.16 Among those who received care and struggled to afford it, 73 percent reported making difficult trade-offs, like scaling back on food, clothing or other basic necessities.17 Low-income earners are hit the hardest, but studies show that middle-income households struggle as well.18 Undeniably, healthcare affordability is a top-of-mind consumer concern.19

Addressing unit price growth isn’t easy, particularly when healthcare providers, drug makers and device manufacturers have significant market power. Our accompanying Easy Explainer, Strategies to Address High Unit Prices: A Primer for States, highlights approaches that show particular promise.

Notes

1.Dugan, Andrew, Cost of Healthcare Is Americans' Top Financial Concern, GALLUP (June 23, 2017). https://news.gallup.com/poll/212780/cost-healthcare-americans-top-financial-concern.aspx. See also: GALLUP, Healthcare System, https://news.gallup.com/poll/4708/healthcare-system.aspx (accessed on Nov. 1, 2018).

2. Quincy, Lynn, Why are Healthcare Costs an Urgent Problem?, Easy Explainer No. 2, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub (May 2015). http://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/advocate-resources/publications/why-are-health-care-costs-urgent-problem/

3. The Healthcare Cost Institute’s 2016 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report (January 2018) documented reduced utilization of inpatient services, outpatient services and “professional services” within the employer-sponsored market from 2012-2016. Utilization of prescription drugs, however, increased during the measured period. See: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1vi3S2pjThLFVwB7OtYwFmOiLVPTFl_wk/view

4. Roehrig, Charles, and David Rousseau, “The Growth in Cost Per Case Explains Far More of U.S. Health Spending Increases Than Rising Disease Prevalence,” Health Affairs, Vol. 30, No. 9 (September 2011).

5. Yamamoto, Dale H., Health Care Costs -- From Birth to Death, Health Care Cost Institute (June 2013). https://www.healthcostinstitute.org/images/easyblog_articles/134/Age-Curve-Study_0.pdf

6. Barnett, Jessica C., and Edward R. Berchick, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2016, United States Census Bureau (September 2017). https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/demo/p60-260.html

7. Service categories include: prescription drugs, inpatient hospital services, outpatient services and professional services.

8. Health Care Cost Institute (January 2018).

9. Diamond, Dan, “Medicare’s Cost Surprise: It’s Going Down,” Politico (Sept. 12, 2018). https://www.politico.com/agenda/story/2018/09/12/medicare-spending-cost-budget-000692

10. Medicaid pays providers significantly less than what they receive from private payers. Low reimbursement rates decrease the willingness of some providers to treat Medicaid participants, which can limit enrollees’ access to healthcare services.

11. Ginsburg, Paul B., Wide Variation in Hospital and Physician Payment Rates Evidence of Provider Market Power, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (November 2010). http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/1162/ See also: White, Chapin, James D. Reschovsky, and Amelia M. Bond, “Understanding Differences Between High- And Low-Price Hospitals: Implications for Efforts to Rein in Costs,” Health Affairs, Vol. 33, No. 2 (February 2014) https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0747 and Cooper, Zack, Stuart V. Craig, and John Van Reenen, “The Price Ain’t Right? Hospital Prices and Health Spending on the Privately Insured,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics (September 2018). https://academic.oup.com/qje/advance-article/doi/10.1093/qje/qjy020/5090426

12. Hunt, Amanda, Strategies to Address High Unit Prices: A Primer for States, Easy Explainer No. 14, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub (November 2018). See also: Altarum Healthcare Value Hub, Cost & Quality Problems: Provider Market Power, http://www.healthcarevaluehub.org/cost-and-quality-problems/browse-cost-driverquality-issue/provider-market-power/ (accessed on Oct. 2, 2018).

13. Krishnan, Sunita, Prescription Drug Competition Hampered by Policies, Barriers and Delay Tactics, Easy Explainer No. 13, Altarum Healthcare Value Hub (December 2017).

14. Ibid.

15. MEDPAC, Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, Washington, D.C. (June 2017). http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/jun17_ch7.pdf?sfvrsn=0

16. DiJulio, Bianca, et al., Data Note: Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs, Kaiser Family Foundation, San Francisco, Calif. (March 2, 2017). https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/data-note-americans-challenges-with-health-care-costs/

17. Ibid. See also: Hamel, Liz, et al., The Burden of Medical Debt: Results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey, Kaiser Family Foundation, San Francisco, Calif. (January 2016). https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/8806-the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundation-new-york-times-medical-bills-survey.pdf

18. Quincy (May 2015).

19. Dugan (June 23, 2017). See also: GALLUP, Healthcare System, https://news.gallup.com/poll/4708/healthcare-system.aspx (accessed on Nov. 1, 2018).