Cost & Quality Problems

Low-Value Care

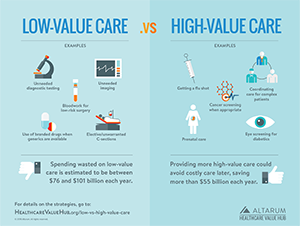

A shocking amount of health care is considered unnecessary. Across several large studies it is estimated that 3% or more of total health care spending is for unneeded services or due to delivery inefficiencies (for example, test results not being shared).1 Services that have been identified as low- or no-value number more than 500, according to the Choosing Wisely campaign.2 Examples include:

- An EEG for a patient with a headache, or a CT scan or MRI for a patient with lower-back pain and no signs of a neurological problem

- Emergency room visits for non-emergencies

- Surgery when physical therapy would be equally or more effective

- Inappropriately prescribed antibiotics

The most egregious form of no-value care is medical harm, addressed here.

How Common Is It?

Studies that examine the prevalence of low- and no-value care typically study just a handful of services.3 Keeping this caveat in mind, recent studies have estimated that 14 to 25% of Medicare beneficiaries and 8% of commercially insured adults experience one or more low-value services in a year.4,5 One study looked at 20 measures of low-value care in a population of children and found approximately 10% of children received at least one low-value service, with similar rates in both Medicaid and privately-insured groups.6

Some low-value services are relatively common. For instance, the over-prescription of antibiotics, which contributes to high costs and growing antibiotic resistance, is highly prevalent, with the CDC estimating as many as half of all antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary or ineffective.7 Similarly, providing opioids to patients with migraine headaches and using antipsychotics to treat dementia, are two low-value services that are prescribed to as many as a quarter of all patients who have the relevant diagnosis. Other services, such as unnecessary cervical cancer screenings, are far more rare.8 In the study of children above, low-value prescription drug use was the most frequent service, followed by diagnostic tests, and last but still showing low-value behaviors — imaging tests.

Overuse of Low-Value Care is Localized

A key finding with implications for addressing this cost-driver is that many studies have found significant geographic variation in the provision of low-value care. In the study of prevalence in children above - while there was no difference by source of health insurance - the authors did uncover differences in low-value practice by state. A study of adults had very similar findings.9 Other studies have found that higher use of low-value services associated with areas of greater overall per capita spending, a higher specialist to primary care ratio and higher proportion of minority beneficiaries.10

These findings suggest that spending on low-and no-value care can be quite a bit higher than the overall average suggest. Moreover, an unnecessary test or scan can be more expensive than first recognized, if it triggers additional care.11

Strategies to Address Low-Value Care

In order to reduce the use of low-value care, we must have some consensus around the list of low-value services, provide accurate information to both physicians and patients regarding the prevalence and risks of these services, and consider financial and non-financial incentives to discourage their use. Moreover, we must continue to build a robust evidence base regarding the clinical effectiveness of treatments. Our strategy discussion has more on these approaches.

By definition, spending on low-value care could be eliminated without worsening health outcomes, freeing funds for investments proven to help address people's goals and needs, like increasing the provision of high-value care and addressing unmet social needs. Failure to curtail this form of waste raises premiums and causes patients to endure unnecessary cost-sharing for services, inconvenience and occasionally medical harm.

Notes

1. Hunt, Amanda, "Six Categories of Healthcare Waste: Which Reign Supreme?" Healthcare Value Hub blog (October 2019).

2. While not the only source for identifying low-value care, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation's Choosing Wisely initiative is one of the most widely recognized. The campaign aggregates recommendations from industry experts on how to reduce low-value care and distributes that information to clinicians and patients. Other efforts to identify low-value care include the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (services rated "D") and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ("do not do" recommendations) in the UK. Low-value care has also been identified in Health Assessments performed by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies and various peer-reviewed medical journals.

3. There is a gap between our ability to identify low-value services and our ability to establish the frequency of these services in claims data. Because there can be a high degree of clinical nuance when working with individual patients, a much smaller subset of low-value services is typically used by researchers working with claims data.

4. Oakes, Allison H., et al., "Systemic Overuse of Health Care in a Commercially Insured US Population, 2010-2015," BMC Health Services Research, (May 2, 2019).

5. One study found that up to 40 percent of Medicare beneficiaries receive a "low-value" health care service each year. See, Schwartz, Aaron L., et al., "Measuring Low-Value Care in Medicare," JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 174, No. 7 (July 2014).

6. Chua, Kao-Ping, et al., "Differences in the Receipt of Low-Value Services Between Publicly and Privately Insured Children," Pediatrics (January 2020).

7. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013."

8. Colla, C. et al., "Choosing Wisely: Prevalence and Correlates of Low-Value Health Care Services in the United States," Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 30, No. 2 (November 6, 2014).

9. Charlesworth, Christinia J., "Comparison of Low-Value Care in Medicaid vs Commercially Insured Populations," JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 176, No. 7 (July 2016).

10. An Australian study found that the Hospital (as opposed to the surrounding geographic area) went furthest in explaining variation in the provision of selected kinds of low-value care. See: Colla, C. et al., "Choosing Wisely: Prevalence and Correlates of Low-Valye Health Care Services in the United States," Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 30, No. 2 (November 6, 2014). See also: Badgery-Parker, Tim, et al., "Exploring Variation in Low-Value Care: A Multilevel Modelling Study," BMC Health Services Research (May 30, 2019). See also: Barreto, Tyler W., et al., "Primary Care Physician Characteristics Associated with Low Value Care Spending," Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, Vol. 32, No. 2 (March 8, 2019).

11. Ganguli, Ishani, et al., "Prevalence and Cost of Care Cascades After Low-Value Preoperative Electrocardiogram for Cataract Surgery in Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries," JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 179, No. 9 (June 3, 2019).