Cost & Quality Problems

Health Inequities

For decades researchers have observed pervasive differences among racial and ethnic minority populations including increased burden of disease, higher mortality rates, lower quality of care and poorer outcomes in the health care system. The CDC defines health disparities as “the preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations. Populations can be defined by factors such as race or ethnicity, gender, education or income, disability, geographic location (e.g., rural or urban) or sexual orientation.”1 Addressing health disparities is a crucial dimension of achieving a patient-centered, high-value health system. In contrast, failure to address health disparities is not only an indicator of low-quality care and an unfair health system, disparities also result in excess costs throughout the health system and society.

Landmark Studies in Health Disparities Research

In 1985, the Department of Health and Human Services released The Secretary’s Task Force Report on Black and Minority Health (the Heckler Report), documenting the existence of, and the extent to which, minorities experienced health disparities. The Heckler report documented the increased burden of illness and death experienced by minority populations. It found six major areas of concern: cardiovascular disease and stroke; cancer; chemical dependency related to cirrhosis of the liver; homicides and accidents, diabetes and infant mortality.

Almost 20 years later, the Institute of Medicine published its landmark report on health disparities, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. In addition to supporting previous documentation of the burden of illness and death for minorities, this report found that ethnic minorities experience lower quality of care. If the individual is a person of color, after controlling for socioeconomic status and other indicators, it predicted the quality of care received by the health system.

The Heckler Report and Unequal Treatment are seminal studies within an extensive body of research documenting the health disparities experienced by socially disadvantaged populations in the US. Selected studies below demonstrate the ways health disparities manifest at all points of the health system.

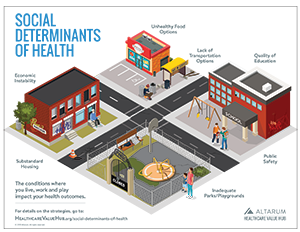

Disparities in Social Determinants of Health

- Urban, low income communities of color have less access to grocery stores and supermarkets, which impacts access to healthy foods, than urban, low income white communities.2

- Research that looked at entry to kindergarten found that Latino, African and African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander kids had lower math and reading scores than white students.3

- American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities experience a violent crime rate that is 2-3 times that of the national average.4

- AI/AN women experience twice the risk of preterm birth than white women, even when controlling for behavioral factors such as pregnancy weigh gain, adequacy of prenatal care, smoking and alcohol use and use of prenatal vitamins.5

Disparities in Access to Care

- 1 in 4 American Indian/Alaska Native adults aged 18-64 do not have health insurance, more than twice the national average.6

- All other racial/ethnic minority groups also experience higher rates of uninsured than non-Hispanic whites. In 2017, non-Hispanic whites had an uninsured rate of 6 percent while the uninsured rates for Asians were 7 percent with Blacks and Hispanics reporting the next highest rates of uninsured at 11 percent and 16 percent respectively.7

- Among those individuals with any depressive disorder, 69 percent of Asians, 64 percent of Latinos, and 59 percent of African Americans did not access any mental health treatment in the past 12 months, compared with 40 percent of non-Hispanic whites.8

- Patients with limited English Proficiency (LEP) report less access to a usual source of care, lower rates of preventive services and fewer physician visits compared to English-speakers in outpatient settings. Even when consumers with a language barrier do have access to care, it is found that they have decreased comprehension of their diagnoses, poorer adherence to treatment, more medical complications and lower satisfaction with care when compared to English-speakers.9

- Blacks are more likely to undergo major surgery at low-quality hospitals than white patients, even when they live closer to a high-quality hospital than their white counterparts.10

Disparities in Treatment by the Health System

- Implicit bias also impacts treatment decisions in the patient/provider setting. In emergency care settings, multiple studies observed that Black and Hispanic patients who entered the ER with similar clinical presentations, and registered the same experience of pain, were less likely to receive analgesia and/or opioids from the treating physician than white patients.11

- In the U.S., 60 percent of low-income women are screened for breast cancer vs. 80 percent of high-income women. But even within the same economic stratum, white women have higher screening rates than African-American and Latino women.12

- There are disparities among racial and ethnic minorities around knowledge and use of preventive services. Data from 17 states showed that Hispanics had the lowest reported rates of having their cholesterol checked and of those with diabetes the lowest reported rates of having a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) test in the past 12 months. American Indian women had the lowest reported rates of mammography screening for women over 40 in the past 24 months. In the past 36 months, Asian and Pacific Islander women had the lowest reported rates of Pap smear screenings.13

- In low-income neighborhoods, patients with diabetes are 10 times more likely to undergo limb amputation than those in affluent areas. Compared to white Americans, the rate of hospitalization for patients with diabetes is twice as high for Latinos and three times higher for African-Americans.14

- In a group of insured women with equal access to treatment, Latina and Chinese women were less likely to receive adjuvant hormonal therapy, a therapy that reduces the risk for recurrence of breast cancer.15

Worse Health Status

- American Indians and Alaska Natives born in 2018 have a life expectancy of 73.0 years, 5.5 years less than the national all races life expectancy of 78.5 years.16

- When compared to whites, the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes is 77 percent higher among African Americans and 66 percent higher for Hispanics. Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Native Hawaiians face twice the risk of developing diabetes when compared to the population overall.17

- Blacks as well as US and foreign-born Hispanics have higher prevalence of impaired cognitive function and physical disability, even when controlling for education and income.18

- A California study found that Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, South Asian and Vietnamese Americans who reported experiencing racial discrimination or LEP, were more likely to report poor quality of life, even when accounting for demographic factors. For South Asians who experience discrimination, they estimated 14.4 more activity limited days per year than South Asians who did not report experiencing discrimination.19

Higher Mortality Rates

- The death rate from breast cancer for African-American women is 50 percent higher than for white women. Racial and economic inequities in screening and treatment options contribute to this divide.20

- Blacks in the US have higher death rates when compared to whites from diabetes, cancer and heart disease, including twice the death rate from diabetes compared to whites.21

- Even when controlling for socioeconomic status and education, the odds that a black woman will die in childbirth is three to four times that of a non-Hispanic white woman.22

- The mortality rate for black men from hypertension is over 50 per 100,000 and 40 per 100,000 for black women compared to 15 deaths per 100,000 for whites. This increased burden of disease persists even when controlling for behavioral, biomedical and socioeconomic risk factors.23

Cost of Failure to Address Health Disparities

The Joint Center for Economic and Political Studies approximated that 30.6 percent of medical care expenditures between 2003 and 2006 for persons of color were excess costs related to health inequalities. The Center also found that if the health system eliminated health disparities it would reduce direct medical care costs by almost $230 billion.24 Research has also looked at the cost of specific health concerns. A study found that reducing disparities in African American workers in effective asthma treatment by 10 percent could save over $1600 per person annually in costs associated with medical expenses and missed work.25 Addressing health disparities is not only the right thing to do but will increase value and quality in the health care system.

Notes

1. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/disparities/index.htm

2. Richardson, et al., Are neighbourhood food resources distributed inequitably by income and race in the USA? Epidemiological findings across the urban spectrum, April 2012

3. Mulligan, et al., First-Time Kindergartners in 2010-11: First Findings From the Kindergarten Rounds of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010-11, July 2012

4. US Department of Justice, Policing on American Indian Reservations, July 2001

5. Bryant et al, Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrical Outcomes and Care: Prevalence and Determinants, April 2010

6. National Health Interview Survey, 2015

7. Berchick et al, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2017, Report Number P60-264, September 2018

8. Algeria et al, Disparity in Depression Treatment Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations in the United States, January 2015

9. Karliner et al, Convenient Access to Professional Interpreters in the Hospital Decreases Readmission Rates and Estimated Hospital Expenditures for Patients with Limited English Proficiency, March 2017

10. Dimick et al, Black Patients Are More Likely to Undergo Surgery at Low Quality Hospitals in Segregated Regions, June 2013

11. Chapman et al, Physicians and Implicit Bias: How Doctors May Unwittingly Perpetuate Health Care Disparities, November 2013

12. Pearl, Robert, Why Health Care Is Different If You're Black, Latino Or Poor, March 2015

13. Liao et al, Surveillance of health status in minority communities - Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) Risk Factor Survey, United States, 2009, May 201

14. Bakalar, Nicholas, Disparities in Diabetes, August 2014

15. Livaudais et al, Racial/ethnic differences in initiation of adjuvant hormonal therapy among women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, January 2012

16. Indian Health Service, April 2018

17. Thorpe et al, The United States Can Reduce Socioeconomic Disparities By Focusing On Chronic Diseases, August 2017

18. Crimmins et al, Race/Ethnicity, Socioeconomic Status, and Health, 2004

19. Gee, Gilbert and Ninez Ponce, Associations Between Racial Discrimination, Limited English Proficiency, and Health-Related Quality of Life Among 6 Asian Ethnic Groups in California, September 2011

20. Pearl, Robert, Why Health Care Is Different If You're Black, Latino Or Poor, March 2015

21. Artiga et al, Key Facts on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity, June 2007

22. Chalhoub, Theresa and Kelly Rimar, The Health Care System and Racial Disparities in Maternal Mortality, May 2018

23. Hicken et al, Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hypertension Prevalence: Reconsidering the Role of Chronic Stress, January 2014

24. LaVeist et al, The Economic Burden Of Health Inequalities in the United States Fact Sheet, 2011

25. Nerenz et al, A Simulation Model Approach to Analysis of the Business Case for Eliminating Health Care Disparities, March 2011