All-Payer Claims Databases: Unlocking Data to Improve Healthcare Value

Meaningful health system improvements are hindered when systematic information about prices, quality and utilization levels are not available. All-payer claims databases (APCDs) are an important tool for revealing spending flows within a state and measuring progress over time. To fully realize their value, implementation of an APCD requires broad stakeholder engagement, sufficient funding, participation by consumer representatives, and extensive data access so that the data can be used for a variety of public purposes. APCDs are a necessary step to building healthcare transparency in states.

Every year, billions of lines of healthcare data are generated when healthcare services are billed and paid by insurers. These claims data contain a wealth of information about what services are being provided and what they cost. But these data are often locked up in proprietary datasets owned by insurers or aggregators that often deny access or charge high prices.

All-payer claims databases (APCDs)1 are used to unlock this data by collecting healthcare claims and other data into databases that can be used by a wide variety of stakeholders to monitor and report on provider costs and the use of healthcare services. Armed with this information, policymakers, regulators, payers and other key stakeholders can begin to address unwarranted variation in prices, healthcare waste and other consumer harms.

What are All-Payer Claims Databases (APCDs)?

APCDs are large-scale databases created by states that contain diverse types of healthcare data (see Exhibit 1).2 APCDs usually contain data from medical claims with associated eligibility and provider files. APCDs may also include HMO encounter data and/or pharmacy and dental claims.3 All-payer claims databases differ from insurers' proprietary claims databases in that APCDs bring together data from multiple payers and are assembled and managed in the public interest.

When the data includes Medicaid and Medicare claims as well as fully insured and self-insured commercial claims we call it an all-payer claims database. When it includes only some of these payers it is referred to as a multi-payer claims database. Generally, APCDs are created through state legislation, although in some circumstances they are created by voluntary data reporting arrangements.

Exhibit 1:

|

Who Finds this Information Useful and Why?

All-payer claims databases are beneficial for a wide range of stakeholders, including policymakers, consumers, payers and researchers, and have been touted as a key part of health system transformation because they increase healthcare spending transparency and help inform decision making.

Consumers can benefit from the increased price transparency that APCDs provide, particularly when the data is used to create a consumer-friendly website that enables them to compare cost information for specific procedures across providers. More importantly, they benefit indirectly when the data in the APCD is used by other stakeholders to reduce pricing variation or improve quality.

Policymakers and regulators can use APCD data for a wide variety of purposes. A key use is to understand the health pricing landscape in their state and identify areas of unjustifiably high costs.

For example, policymakers can use all payer claims data to understand and evaluate the effects of state efforts to improve value for consumers. APCD provide a complete picture of health spending in a state, enabling them to evaluate if efforts to control spending in one area represent a net improvement, or whether those efforts lead to spending increases somewhere else. Finally, policymakers can also gain a better understanding of the health status and disease burden of their state population, in order to reduce health disparities and otherwise improve the general health of state residents. Conversely, in the absence of APCD data, state policymakers and others are limited in their ability to monitor state progress on these vital issues.

Payers may be interested in a more complete picture of spending and provider practice patterns than they can glean from their own claims and encounter data.7 For example, they might use hospital cost data to identify high- and low-value hospital's’, successful cost containment strategies, or the prevalence of different diseases at a state level. In addition, employers have used APCDs to track progress of cost, quality and preventive service measures across their employee populations. Employers may also use health status and disease prevalence information to create wellness programs or other targeted interventions for their employee populations.

Researchers are interested in this information in order to study the outcomes of state or federal health reform initiatives on spending and quality, to gain a deeper understanding of disease prevalence or other public health issues, or to better understand provider pricing variations, among other issues.8

What Does the Evidence Say About the Impact of APCDs?

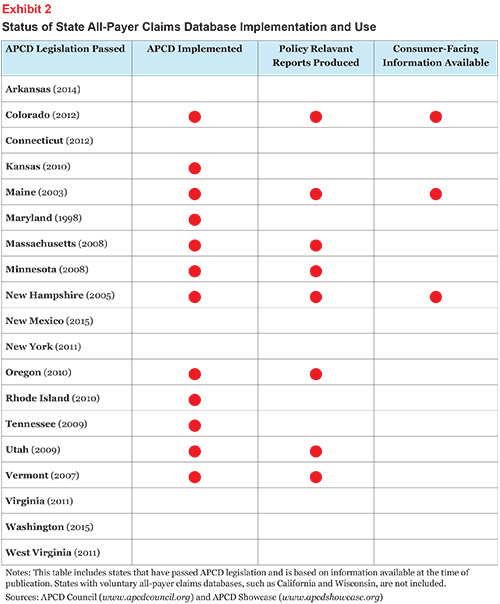

All-payer claims databases are a fairly recent innovation with few states having broad implementation (see Exhibit 2). Hence, they are just beginning to provide information for valuable research on trends in cost, quality and utilization. Nonetheless, the APCD Council—a learning collaborative of government, private, nonprofit and academic organizations focused on improving the development and deployment of state-based APCDs—has catalogued more than 40 research studies on the impact of APCDs.9

Below are some examples of reports that have been produced using data from APCDs:

-

Vermont: Using APCD to Inform Rate Review

Vermont used funds from an ACA rate-review grant to investigate how their multi-payer claims database could inform the rate-review process, such as improving their ability to validate insurance company rate filing applications, medical trend analyses, and generating comparative data for benchmarks.10

-

New Hampshire: Cost Evaluations

State agencies have created reports from their APCD that focus on healthcare service and health insurance premium costs and costs drivers, enrollment trends and disease patterns.11 New Hampshire also commissioned a study that allowed the Medicaid agency to compare its provider rates with those of the commercial payers when revising its fee schedule.

-

Utah: Population Health

The Utah Department of Health published a report enabling stakeholders to understand the Utah population in a new way.12 Specifically, the report examined the healthy population of Utah—and their exact location within the state—to identify what specific preventative and routine healthcare they are receiving to keep them healthy.

-

Oregon: Reports for Policymakers The Oregon Health Authority published a report using APCD data that examines the outcomes of health system transformation efforts.13

Much has been made of consumer-facing websites that enable consumers to compare prices. While providing clear, actionable information on prices is a worthy goal and only fair to consumers, it is important to realize that only a small portion of overall spending is “shoppable” by consumers.14 Moreover, a number of barriers exist to providing actionable information to consumers. Two evaluations of the New Hampshire website (an early example of a consumer-facing pricing website) found that consumer use of the website has been modest and has yet to encourage consumer price-shopping.15 The evaluations found, however, that the data was useful to policymakers by highlighting the wide gaps in provider prices in the state.

Issues to Consider in APCD Development

Creating all-payer claims databases is foundational to informing other strategies designed to improve healthcare value for consumers. Implementing these databases involves a host of decisions, all with profound impact on the value of the resulting database.

For states that haven’t enacted APCD legislation, there are several issues to consider, including the development goals, governance and administration, the scope of data collected, funding sources, privacy issues and reporting requirements. For states that have already enacted APCDs, consider whether or not adjustments need to be made to the overarching structure.

Establish Broad APCD Goals

All-payer claims databases can be developed with broad or narrowly defined goals. For example, the goal of Minnesota’s APCD is to provide more information to the state’s health department, and data use is limited to this department.16 On the other end of the spectrum, Maine’s APCD was developed with the broad goal to improve the health of Maine citizens.17

Advocates should work towards an APCD with broad goals and tie it directly to improved health value for the state’s citizens and its government. Experts agree that states need to design APCDs based on a common vision of use and agreement on how the dataset will provide value to a broad groups of stakeholders.18

APCD Governance With Consumer Involvement

The governance structures of existing APCDs vary widely (see below for descriptions of typical governance models). Most states with existing APCDs have chosen to have an oversight body that has the authority to collect and disseminate the data. The organization housing the data is typically a state agency, such as the department of insurance or the health department, or an independent nonprofit APCD administrator. Ongoing conversations with stakeholders about measurement strategies, reporting requirements and processes, and projected timelines help to build consensus about the approach and focus of data uses.19

The governance model should be tailored to local conditions but in all instances should include consumer representation on the board or advisory group.

Four Models of State APCD GovernanceModel 1: State Health Data/Policy Agency Management Legislation authorizes the state agency or health data authority to collect and manage data, either internally or through contracts with external vendors. Legislation grants legal authority to enforce penalties for noncompliance and other violations, while separate regulations define reporting requirements. A statutory committee or commission is defined in law, or the state agency appoints an advisory committee. States with this model include Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oregon, Tennessee and Utah. Model 2: Insurance Department Management The APCD is managed by a state agency responsible for the oversight, regulation and licensing of insurance carriers. Advisory committees of major stakeholders guide decisions. Reporting is mandated under the authority of the Insurance Code, with penalties for noncompliance. The only state with this model is Vermont. Model 3: Shared Agency Management Two state agencies with separate authorities share in the governance and management of data collection, reporting and release—such as an agency with health insurance claims expertise and one charged with tracking and improving health status of state residents. The shared responsibilities are defined in statute and expanded on in a Memorandum of Understanding that further defines the scope of authority and the process of decision making. In New Hampshire, for example, the agencies are the Department of Health and Human Services and the Insurance Department. Model 4: Private APCD Initiatives A private APCD initiative may be established in states without legislative authority. Data are collected voluntarily from participating carriers with no authority to leverage penalties for nonreporting. A board of directors composed of all major stakeholders guides the decision-making process. Examples of this model include the Wisconsin Health Information Organization and the Washington Health Alliance. Source: Love, Denise, et al., “All-Payer Claims Databases: State Initiatives to Improve Healthcare Transparency,” The Commonwealth Fund (2010). |

Establishing Sustainable APCD Funding

Adequate funding is essential to the success of an APCD. The goal for each state is to build a sustainable APCD system that provides consistent and robust information across the state’s healthcare system over time. Funding requirements vary greatly but could range from $500K to establish a bare-bones system to several million dollars.20

States should identify funding sources as part of the legislative process. Public APCDs may be funded with appropriations or industry fees and assessments. States can also write a non-compliance financial penalty into their legislation to be levied on payers who do not meet the reporting requirements. States may also be able to take advantage of Medicaid matching funds.

Some states expect a portion of APCD funding to come from the future sales or licensing of data products. Another option, used by Wisconsin’s voluntary APCD, is funding through subscription and membership fees. However, this method of funding may include restrictions on the use of data (see below).

APCD Data Access and Privacy Issues

Claims data contains sensitive personal information. Determining how to protect consumers’ privacy while establishing APCDs is one of the most important issues states will face.

States must decide who will be able to access the APCD data and for what purposes.

There is wide variation in state approaches on this matter.

Minnesota only allows the state health department to access their APCD data, a policy which might be seen as a way to protect patients’ privacy but also greatly restricts the ways in which the data can be used. In contrast, both Maine and New Hampshire publish aggregated payment data on a public website where anyone can access it.

About half of the states with APCDs currently only allow de-identified patient information to be collected. This limits the ability to track treatment, outcomes and disparities over time and to drill down on policy implications. To address this problem, while protecting patient privacy, the trend seems to be towards allowing patient identifiers--a number assigned to each patient that is not linked to personally identifiable information.21 This allows for better long-term tracking and connecting with public health and clinical data, all of which is very useful for researchers and other stakeholders.

It is critical that APCD consider broad data access policies to ensure that the value of the data is fully realized. Once privacy considerations are addressed, a variety of stakeholders should be able to access the data at as detailed a level as possible. Further, states should use the data for regular reports and analyses so that policymakers and regulators begin to incorporate these findings into their work.22

Incorporating Medicare and Medicaid Data

The APCD Council recommends the inclusion of Medicaid and Medicare claims data to get a more complete picture of a state’s practice patterns and spending. Medicare's fee-for-service program accounts for one fifth of all healthcare spending. Recent changes at CMS have made it easier to obtain Medicare claims data information.23 The submission of Medicaid data to the APCD should be coordinated with the state office that stewards the Medicaid data.

Incorporating Encounter Data

Plans that operate under capitation (e.g., a staff-model HMO) do not generate claims in the usual sense. States such as Colorado are working on protocols that allow this data to be added to the APCD for a more complete picture of spending and practice patterns.24

Pharmacy and Dental Data

Pharmacy and dental claims are often generated using a separate system from medical claims and APCD operators will have to explicitly include this data in the data reporting requirements to ensure a complete picture of spending. The APCD Council has been working to create standards that require the collection and inclusion of this information.25

Data Standardization

A non-uniform approach for APCD data submission can mean increased costs to all stakeholders. If each state uses a “one-off” data collection, data cannot be easily merged or analyzed across states. Different extracts must be created for each data collection entity, costs for payers submitting data, especially for payers that are operating in multiple states.

In an effort to bring standardization to the APCD data collection process, the APCD Council worked with other entities to establish reporting APCD guides for eligibility as well as medical, pharmacy and dental claims files.26

Including Healthcare Quality Information

Claims data, by itself, has the ability to provide some limited quality signals, such as identifying areas of overtreatment or inappropriate treatment (such as overuse of CT scans or Caesarean sections), find patterns of preventable medical errors and harm and tally the associated cost.

A next step for APCDs is be to integrate other non-claims data sources, such as patient registries, vital records, clinical data, and patient reported surveys.27 While challenging, the combined data provide an opportunity for even more valuable analysis.

States like Massachusetts and Colorado are currently working on developing patient safety and quality reports by incorporating data from other sources. For example, combining electronic medical records with claims data to identify opportunities for improving outcomes for Medicaid patients.28 The NH Hospital Scorecard allows consumers to view patient satisfaction, patient safety and clinical quality measures.29

Other possibilities include identifying conflicts of interests that might be driving prescribing or testing patterns. With access to data, researchers can correlate the introduction of a new drug with pharmaceutical sales practices, and discover if there is a pattern of inappropriate prescribing by an individual physician. As important, the data could expose a link between tests and whether or not the referring doctor has a financial stake in the testing lab.

Supporting Health Equity Work

Demographic data, such as race, ethnicity and language preference may also be incorporated into an APCD. This data enables researchers to identify health disparities, and provide evidence for public health and institutional interventions. This data can be collected at the point of enrollment into health insurance programs, as well as at the point of care. However, the collection of this data is not currently standardized; efforts to do so are increasingly found at the state level.

Voluntary Efforts Are More Challenging

APCDs are generally created by state legislation, although in some circumstances they are created by voluntary data reporting arrangements.30

In general, strong legislation will yield a more robust dataset than voluntary efforts. Voluntary initiatives cannot compel data submission by all payers in a state and thus the data can be incomplete. Further, the use of aggregated data may be restricted if one or more contributors of data oppose public release. APCD data often have de-identified personal health data in order to track service use over time. Privacy laws make it difficult for private entities to receive and release de-identified patient data without legal authority.

Examples of states that have established an APCD based on a voluntary basis:

-

Wisconsin: In 2005, the Wisconsin Health Information Organization (WHIO) was created voluntarily by providers, employers, payers and the state to improve healthcare transparency, quality and efficiency in the state. WHIO members and subscribers use the data to identify gaps in care for treatment of chronic conditions and provide real-world data about per episode costs of care, population health, preventable hospital readmissions, variations in prescribing patterns and much more.

-

California: The nonprofit California Healthcare Performance Information System (CHPIS), founded in 2012 by three of the largest health plans in California and the Pacific Business Group on Health, serves as a voluntary multi-payer claims database. In 2013, CHPIS acquired its first year of CMS fee-for-service Medicare data—for over five million California beneficiaries—and commercial claims for HMO, POS, PPO, Medicare Advantage products from Anthem Blue Cross, Blue Shield of California and United Healthcare. It does not have data on “allowed amounts” or provider fee schedules, but is focused on quality, efficiency, and appropriateness of care. Plans and purchasers have two thirds of the seats on its board, with providers and a consumer group making up the other third. The first public report on physician-level quality ratings is expected later in 2015.

-

Washington: The Puget Health Alliance, established in 2004, helped to created a purchaser-led, multi-stakeholder collaborative, voluntary APCD. The database comprises approximately 65 percent of the non-Medicare claims in the region. The Alliance changed its name to the Washington Health Alliance and expanded its activities statewide and access to the Alliance’s database by researchers and other interested parties is possible but is very limited. In May 2015, the state instituted a law that establishes an APCD and mandates a strict requirement that all health insurers must submit data.

Limitations of APCDs

Capturing Spending By Uninsured

It is almost impossible for an APCD to capture spending by uninsured individuals because their visits to providers do not generate a “claim” that goes to an insurance company.

Maine is the only state that has incorporated uninsured claims, and then only partially. Maine Health provides identification cards to uninsured individuals using their services to better manage their care and to document uncompensated care. Maine Health then submits pseudo-claims to a third-party administrator (TPA) owned by a national insurer for processing as if they were from insured patients, but no payment is made. Summary information on the uninsured patients is produced by the TPA for Maine Health and claims data files are submitted to the state APCD. From a policy perspective, capturing data on the uninsured is important and Maine has the potential to be a model for the rest of the states.

Denied Claims

Denied claims are typically not included in APCDs. While the inclusion of denied claims would increase researcher and regulators’ ability to access health plan’s role in spending flows, their inclusion would increase the amount of data that would have to be collected and stored.

Conclusion

Policymakers and other stakeholders need access to information on healthcare spending in their state to better understand their unique healthcare market and to help make more informed decisions. It is well established that there are wide variations in treatment patterns and what providers charge for the same procedure. It is also well established that much of our healthcare spending is wasteful and that many providers do not align with evidence-based quality standards. State policymakers need to step into this void by enacting and funding robust APCDs that can help them pursue initiatives to bring better healthcare value to the residents of their state.

All-payer claims databases have the potential to help inform significant changes that will benefit consumers, however inadequate funding, overly restrictive data release policies and other issues related to the ability to collect data have restricted APCDs from reaching their full potential as policy making tools.

Notes

1 Although we use the term “All-Payer Claims Databases” throughout this issue brief, it is also important to include encounter data from HMOs and integrated systems, such as Kaiser, that do not have claims submitted.

2 Miller, Patrick, Why State All-Payer Claims Databases Matter to Employers, The Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. (2012).

3 Ibid.

4 Love, Denise, et. al., All-Payer Claims Databases: State Initiatives to Improve Healthcare Transparency, The Commonwealth Fund (September 2010).

5 Miller, Patrick, et. al, “All-Payer Claims Databases: An Overview for Policymakers,”, AcademyHealth (May 2010).

6 Love (September 2010).

7 Miller (May 2010).

8 Ibid.

9 APCD Showcase Website (http://www.apcdshowcase.org/).

10 Kennedy, Lisa, and James Highland, Assessment of Vermont’s Claims Database

to Support Insurance Rate Review, Vermont Department of Banking, Insurance, Securities & Healthcare Administration

(July 2011).

11 Tu, Ha, and Johanna R. Lauer, Impact of Healthcare Price Transparency on Price Variation: The New Hampshire Experience, Center for Studying Health System Change (November 2009).

12 Utah Department of Health, Utah Atlas of Healthcare: Making Cents of Utah's

Health Population (October 2010).

13 Oregon Health Authority, Leading Indicators for Oregon’s Healthcare Transformation, http://www.oregon.gov/oha/OHPR/RSCH/docs/All_Payer_all_Claims/Leading_Indicators_April_2

14 See Consumers Union, What’s the Case for Price Transparency In Healthcare?, forthcoming October 2015.

15 White, Chapin, et al., Healthcare Price Transparency: Policy Approaches and Estimated Impacts on Spending, WestHealth Policy Center (May 2014).

16 Minnesota Department of Health, FAQ All Payers Claim Databases

17 State Health Access Data Assistance Center, Maine’s Healthcare Claims Database Website

18 The Network for Excellence in Health Innovation, All Payer Claims Databases: Unlocking the Potential, Issue Brief (December 2014).

19 Green, Linda, et al, Realizing the Potential of All-Payer Claims Databases,The Robert Wood

Johnson Foundation (January 2014).

20 For more information, see: APCD Council, Cost and Funding Considerations for a Statewide All-Payer Claims Database (APCD) (March 2011).http://www.apcdcouncil.org/file/79/download?token=UUNHTnXi

21 Miller (2012).

22 Green (2014).

23 The Commonwealth Fund, In Focus: Medicare Data Helps Fill in Picture of Healthcare

Performance (April/May 2013).

24 Center for Improving Value in Healthcare, Colorado All Payer Claims Database Annual Report 2014, (February 2015).

25 Learn more about the APCD Council’s Proposed Core Set of Data Elements for Data Submission at http://www.apcdcouncil.org/sites/apcdcouncil.org/files/media/apcd_council_core_data_elements_5-10-12.pdf

26 APCD Council Standards (https://www.apcdcouncil.org/standards)

27 The next step for APCDs will be to integrate other non-claims data sources, such as patient registries, vital records, clinical data and patient reported surveys.

28 APCD Council Showcase, Combining Electronic Medical Records with Claims Data to Identify Opportunities for Improving Outcomes for Medicaid Patients (September 2013).

29 APCD Council Showcase, Scorecard,http://www.apcdshowcase.org/content/nh-hosptial-scorecard-website

30 Peters, Ashley, et al., “The Value of All-Payer Claims Databases to States,” North Carolina Medical Journal (Sept. 5, 2014).