Community Level, Multi-Stakeholder Approaches to Improve Healthcare Value

It is well established that social determinants of health are significant drivers of healthcare cost and quality variation, as well as health inequities. States and local communities are experimenting with broader approaches to achieving uniformly high health outcomes. One example is “social-medical” models of care that typically target high utilizers and use an integrated care team to break down silos between health and social services, assess unmet social needs and provide pathways to housing support, nutrition and other social services.1

Multi-stakeholder collaborations take this idea one step further. They address a broader population and involve stakeholders beyond case managers and providers, such as schools, employers and the local public health agency. These models have grown in popularity in recent years as states test innovative approaches that promote community engagement and improved health outcomes.2

What are Multi-Stakeholder Collaborations?

At their core, multi-stakeholder collaborations are a community-based approaches to achieving population health. Some initiatives also pursue health equity or health system efficiency goals. These regional partnerships may embrace public health, education, housing and other social services sectors in pursuit of these objectives.

Multi-stakeholder collaborations seek to align clinical and community-based organizations around goals and offer an integrated and consumer-centered approach to health, healthcare and social needs.3 For example, Maryland’s Healthy Montgomery initiative identified the “Health in All Policies (HiAP)” approach as a key methodology in its strategic plan.4 The goal of Health in All Policies is to ensure that all decisionmakers are informed about the health, equity and sustainability consequences of various policy options during the policy development process.5 This emphasis stresses consideration of all factors that contribute to a healthy community through increased multi-sector collaboration and stakeholder engagement.

These models are referred to using various terms, and they vary widely according to the role of the backbone organization, funding sources, populations served and overall focus (see taxonomy table). This environmental scan explores these variations but also identifies the structural commonalities, profiles some successful programs and discusses strategies to expand the use of this approach to better public health.

Participating Stakeholders

Multi-stakeholder collaborations feature partnerships within health and social services to serve a geographically defined population. Stakeholder engagement requirements are sometimes impemented by local government mandates or by the funder, elevating the role of selected stakeholders in the collaborative process.

Some states require accountable health structures to partner with providers and health plans to prioritize delivery system reform.6 Multi-stakeholder collaborations may also draw from their provider partners in establishing work groups and task forces to develop strategies to improve access to primary care and address health equity issues.7

Community-based organizations, which include, but are not limited to, organizations focused on minority health and underserved communities, housing, food and nutrition or obesity prevention, are other key stakeholders. Depending on the collaboration’s stated focus and goals, local businesses and schools can also sign on as partners either through financial means or by publically pledging their commitment. Partnerships with local school districts and/or businesses typically focus on wellness goals like obesity and chronic disease prevention.

Backbone Organization

The backbone organization—also know as the convener—is responsible for coordinating and integrating participating stakeholders.8 The backbone organization is essential to ensuring stakeholders’ alignment and active engagement in the agreed-upon priorities, which generally include delivering improved care coordination, enabling healthy behaviors and improving economic opportunity within the community. Most importantly, they manage the pooled financial resources and performance indicators used to measure progress over time.9

Funding

Multi-stakeholder collaborations require financial support for both their start-up costs and continued implementation of selected interventions. Funding can come from state and federal sources—such as State Innovation Model (SIM) grants and CMS Section 1115 DSRIP Medicaid waivers—or from private-sector sources, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), local hospitals and health systems, as well as foundation grants and other private stakeholders in the community.

Federal funding typically includes some restrictions, including defined eligibility criteria or specific implementation requirements, whereas private funding is typically less restricted.

Focus Areas and Goals

The focus and goals of multi-stakeholder collaborations vary according to the funding sources (see table). For example, most federal funding for these initiatives is directed towards Medicaid beneficiaries. Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organizations (CCOs), funded through a State Innovation Model (SIM) grant, consist of broad networks healthcare providers (primary care, addiction, mental health, etc.) who have agreed to work with Medicaid beneficiaries in their local communities.10

But SIM funding can also finance initiatives that target a broader population. SIM funding is intended to transform the health system, address unmet social needs and promote health equity.11 Whereas another CMS-fundedinitiative, Accountable Health Communities (AHCs), are required to focus specifically on providing “navigation services” to assist high-risk individuals access community services.12

On the other end of this spectrum are Accountable Care Communities (ACCs), public-private partnerships between a county and local healthcare, business and other community stakeholders. ACCs emphasize shared responsibility and mobilize the entire community to address specific goals, such as obesity prevention.13 Typically, these models are not dependent on healthcare systems adopting provider payment reforms, but instead rely on stakeholder participation and engagement. These approaches are often coordinated through local public agencies and prioritize addressing the social determinants of health to achieve population health goals.

Conducting both individual and community-level needs assessments are a key component in determining multi-stakeholder collaborations’ priorities and focus areas.

Data and Evaluation

Developing efficient data systems are essential for multi-stakeholder collaborations to inform operations and meet performance goals.

A unique approach to data integration and collaboration support is the Patient Care Intervention Center (PCIC) in Texas. PCICserves local governments, health systems and health plans through data integration services. PCIC’s data infrastructure platform collects data from school districts, county jails, homeless services, police, fire and EMS services and identifies high-need/high-cost patients through the development of data dashboards.14 They also facilitate collaboration through a “Master Client Index,” a secure repository of all individuals with linked records across these multiple systems. They are an exemplar for how social and medical data can be collected and analyzed to provide a “big picture” view of how individuals interact with social support systems.

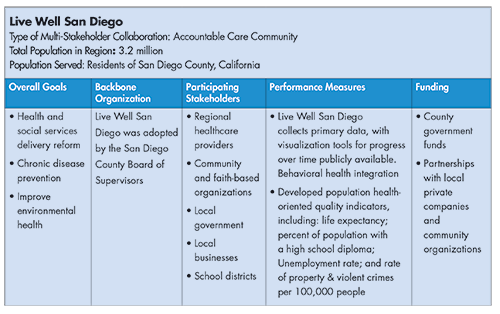

The most successful collaborations not only have data systems to support coordinated operations but also clearly define performance indicators and set measurable short- and long-term goals to benchmark their progress. For example, Live Well San Diego, a collaboration based in San Diego County, California, developed an information exchange that coordinates care teams and optimizes case management by bringing data together from multiple sources. Although the exchange is primarily used internally by case managers, there are opportunities to use its client-facing interface for push alerts, notifications and other features that will improve adherence to clinical or social service recommendations and ultimately improve health outcomes (see box for more information on the Live Well San Diego initiative).

Live Well San Diego also defines multiple indicators to measure performance over time. These includelowering the percentage of residents experiencing food insecurity, as well as increasing the county’s overall life expectancy and percentage of residents healthy enough to live independently. While population health measures like these require long-term measurement to demonstrate improvement, Live Well San Diego created a stable infrastructure that facilitates this longer perspective.

Often, the primary area of focus determines the performance measures used by the collaboration. For example, Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organizations (CCO) report on 17 incentive measures focused on disease prevention and chronic disease management. All CCO’s in the state use the same measures, developed by a central Metrics and Scoring Committee, as mandated by the state.15

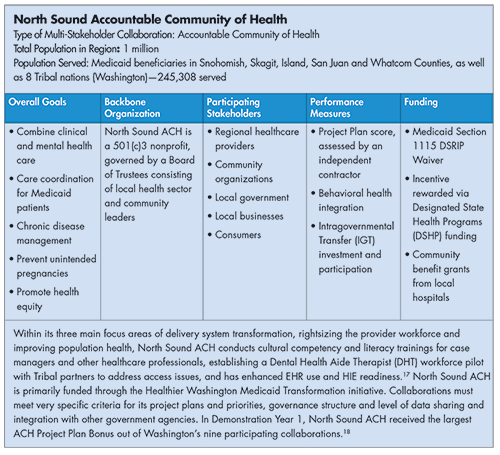

Washington’s Accountable Communities for Health (ACHs) also face distinct performance measures under the state’s Section 1115 grant.16 These performance measures are tied to incentive payments. See box below for a profile of Washington’s North Sound ACH, a multi-stakeholder collaboration serving Medicaid recipients in the northwestern region of the state.

When collaborations need to demonstrate return on investment or cost effectiveness, developing performance measures is more difficult. Many programs lack the infrastructure to define and measure the most relevant outcomes and accurately estimate cost savings.19 Some organizations track hospital utilization data (e.g., ED use, preventable hospitalizations, excess hospital stays), high-cost imaging or drug use to assess program performance.20

Challenges

Evaluations to date are few.21 Nonetheless, researchers have identified some common challenges for further adoption and viability of these models. These include financial sustainability and improving interoperability and further integrating information technology.

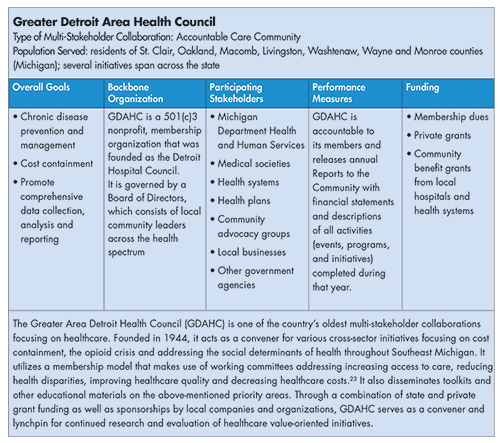

Financial sustainability: While multi-stakeholder collaborations in many states receive SIM grants or other state/federal funding, they also report difficulties meeting the social and logistical needs of their population beyond the start-up phase.22 Because grants typically operate in one to three-year cycles, collaborations often shape action plans around their funding instead of the activities themselves. Pursuing partnerships with local stakeholder and private entities may provide more stable, longer-term financing. An example of this strategy is the Greater Detroit Area Health Council (GDAHC), which employs a membership model to supplement their private grant and state funding streams (see box below).

Improving interoperability and further integrating information technology: Multi-stakeholder collaborations describe difficulty integrating data from electronic health records (EHRs), claims data, health information exchanges (HIEs), and other sources. As mentioned above, doing so is essential to reduce the risk of duplicating efforts within community based organizations or healthcare providers.

Recommendations

At their core, multi-stakeholder collaborations are a community-based approach to achieving population health goals. In doing so, collaborations may also address healthcare efficiency goals and/or health equity. Recommendations for success include:

Ensure community participation and buy-in through advisory groups: Consumers can ensure that their multi-stakeholder colalborations are consumer-driven and -oriented through participation on steering committees and advisory groups that determine the initiative’s strategic plan and directives. For example, Washington’s Accountable Communities for Health, which cover the entire state and are aligned with their Medicaid Regional Service Areas, are each governed by a variety of advisory committees staffed by local community leaders as well as those within the health sector. Engaging community members and advocates ensures continued support and efficacy of multi-stakeholder collaborations’ overall approach and strategy.

Broaden funding by expanding partners and contributors: Funding uncertainties and data sharing issues can hinder multi-stakeholder collaborations and prevent meaningful progress towards their goals. Partnerships with local businesses can shore up funding streams and open opportunities to engage community members in chronic disease prevention initiatives while improved coordination with healthcare stakeholders can serve more health system efficiency-oriented goals. Aspiring multi-stakeholder collaborations need to critically assess existing and potential partners in their specific locales to determine what they can bring to the table.

Conclusion

Accountable Health Structures or multi-sector collaborations are a key approach for improving population health by surfacing population needs and aligning a broad range of stakeholders to address those needs. Other goals can include improving health equity and realizing better healthcare value. Despite the very limited evaluation data, a multi-sector approach seems essential to achieve goals where success is determined by social, economic and environmental factors.

1. Healthcare Value Hub. Addressing the Unmet Medical and Social Needs of Complex Patients, Research Brief No. 17 (February 2017)..

2. Clary, Amy, Tina Kartika, and Jill Rosenthal, State Approaches to Addressing Population Health Through Accountable Health Models, National Academy for State Health Policy, Washington, D.C. (January 2018). https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Accountable-Health-Models.pdf

3. Mongeon, Marie, Jeff Levi and Janet Heinrich, Elements of Accountable Communities for Health: A Review of the Literature, National Academy of Medicine Perspectives, Washington, D.C. (November 2017). https://nam.edu/elements-of-accountable-communities-for-health-a-review-of-the-literature

4. Healthy Montgomery, Health in All Policies, http://www.healthymontgomery.org/

5. Rudolph, Linda, et al., Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments, American Public Health Association and Public Health Institute, Washington, D.C., and Oakland, CA, (2013). https://www.phi.org/uploads/files/Health_in_All_Policies-A_Guide_for_State_and_Local_Governments.pdf

6. Spencer, Anna and Bianca Fredo, Advancing State Innovation Model Goals through Accountable Communities for Health, Center for Health Care Strategies, Trenton, N.J. (October 2016). https://www.chcs.org/media/SIM-ACH-Brief_101316_final.pdf

7. Healthy Montgomery, Healthy Montgomery Steering Committee Members, http://www.healthymontgomery.org/index.

8. National Academy of Medicine Perspectives, Elements of Accountable Communities for Health: A Review of the Literature, Washington, D.C. (November 2017).

9. Cantor, Jeremy, et al., Accountable Communities for Health: Strategies for Financial Sustainability, JSI Research and Training Institute, Arlington, VA (May 2015). http://www.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=15660&lid=3

10. Oregon Health Authority, Coordinated Care: the Oregon Difference, http://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/Pages/CCOs-Oregon.aspx (accessed Feb. 19, 2018).

11. National Academy for State Health Policy, State Approaches to Addressing Population Health Through Accountable Health Models, Washington, D.C. (January 2018).

12. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Accountable Health Communities Model, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ahcm/ (accessed March 8, 2018).

13. National Association of Counties, Profiles of County Innovations in Health Care Delivery: Accountable Care Communities, Washington, D.C. http://www.naco.org/sites/default/files/documents/Accountable-Care-Communities.pdf

14. Patient Care Intervention Center, Community Data Xchange, https://pcictx.org/technology/community-data-xchange (accessed March 8, 2018).

15. Oregon Health Authority, Oregon Health Authority 2017 Quality Pool Reference Instructions, http://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/CCOData/2017%20Reference%20Instructions.pdf.

16. Washington State Health Care Authority, Performance Measures, https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/healthier-washington/performance-measures#pmcc-meetings (accessed May 10, 2018).

17. North Sound Accountable Community of Health, Project Plan Submission (September 2017). https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/nsach-project-plan-final.pdf.

18. Washington State Health Care Authority, Healthier Washington Medicaid Transformation Approved Project Plan Scores and Earned Incentives by Accountable Communities of Health (AHCs), https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/DSRIP-DY1-Earned-Incentive-Funds.pdf (accessed May 10, 2018).

19. Amarasingham, Ruben, et al., Using Community Partnerships to Integrate Health and Social Services for High-Need, High-Cost Patients, The Commonwealth Fund (January 2018). http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2018/jan/integrating-health-social-services-high-need-high-cost-patients http://notes3

20. Ibid.

21. Siegel, Beth, et al., “Multisector Partnerships Need Further Development to Fufill Aspirations for Transforming Regional Health and Well-Being,” Health Affairs (January 2018).

22. Center for Health Care Strategies, Advancing State Innovation Model Goals through Accountable Communities for Health, Trenton, N.J. (October 2016).

23. Greater Detroit Area Health Council, Membership & Giving, http://gdahc.org/membership (accessed May 10, 2018).

Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration Profiles